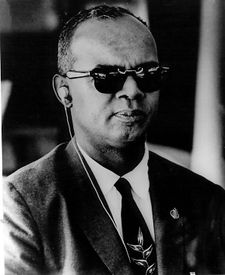

Eric Williams

| Eric Eustace Williams | |

|

|

|

1st Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago

|

|

| In office November 10, 1956 – March 29, 1981 |

|

| Preceded by | Prime Minister established |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | George Chambers |

|

Political Leader of the People's National Movement

|

|

| In office 1955–1981 |

|

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | George Chambers |

|

|

|

| Born | September 25, 1911 Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Died | March 29, 1981 (aged 69) Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Political party | PNM |

| Religion | Anglican |

Eric Eustace Williams (25 September 1911 – 29 March 1981) was the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago. He served from 1956 until his death in 1981. He was also a noted Caribbean historian.

Contents |

Early life

Williams' father was a minor civil servant, and his mother was a descendant of the French Creole elite. He was educated at Queen's Royal College in Port of Spain, where he excelled at academics and football. He won an island scholarship in 1932 which allowed him to attend St Catherine's Society, Oxford (which later became St Catherine's College), where he was ranked first in the First Class of Oxford students graduating in History in 1935, while representing the university in soccer. In Inward Hunger, his autobiography, he described his experience of racism in Britain, and the impact on him of his travels in Germany after the Nazi seizure of power.

Scholarly career

Williams went on to advanced research in history at Oxford, completing the D.Phil in 1938 under the supervision of Vincent Harlow. His doctoral thesis, The Economic Aspects of the Abolition of the Slave Trade and West Indian Slavery, was both a direct attack on the idea that moral and humanitarian motives were the key facts in the victory of British abolitionism, and a covert critique of the idea common in the 1930s, emanating in particular from the pen of Oxford Professor Reginald Coupland, that British imperialism was essentially propelled by humanitarian and benevolent impulses. Williams's argument owed much to the influence of C. L. R. James, whose The Black Jacobins, also completed in 1938, also offered an economic and geostrategic explanation for the rise of British abolitionism.

Despite his extraordinary academic success at Oxford, Williams was denied any opportunity to pursue a career in the United Kingdom. In 1939 he moved to the United States to Howard University ('Negro Oxford' as he called it in his autobiography), where he was rapidly promoted twice, attaining full professorial rank. In Washington he completed the manuscript of his masterwork - Capitalism and Slavery - which was published by the University of North Carolina in 1944. This book slaughtered so many sacred cows of British imperial historiography that it was not until 1964 that it was published in the United Kingdom, and even then, met a hostile reception.

Shift to public life

In 1944 he was appointed to the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission. In 1948 Williams returned to Trinidad as the Commission's Deputy Chairman of the Caribbean Research Council. In Trinidad, Williams delivered a series of educational lectures for which he became famous. In 1955 after disagreements between Williams and the Commission, the Commission elected not to renew his contract. In a famous speech at Woodford Square in Port of Spain, he declared that he had decided to "put down his bucket" in the land of his birth. He rechristened that enclosed park, which stood in front of the Trinidad courts and legislature, "The University of Woodford Square", and proceeded to give a series of public lectures on world history, Greek democracy and philosophy, the history of slavery, and the history of the Caribbean to large audiences drawn from every social class.

Entry into nationalist politics in Trinidad and Tobago

From that public platform, Williams on January 15, 1956 inaugurated his own political party, the People's National Movement, which would take Trinidad and Tobago into independence in 1962, and dominate its postcolonial politics. Until this time his lectures had been carried out under the auspices of the Political Education Movement (PEM) a branch of the Teachers Education and Cultural Association, a group which had been founded in the 1940s as an alternative to the official teachers’ union. The PNM’s first document was its constitution. Unlike the other political parties of the time, the PNM was a highly organized, hierarchical body. Its second document was The People’s Charter, in which the party strove to separate itself from the transitory political assemblages which had thus far been the norm in Trinidadian politics.

In elections held eight months later, on September 24, the PNM won 13 of the 24 elected seats in the Legislative Council, defeating 6 of the 16 incumbents running for re-election. Although the PNM did not secure a majority in the 31-member Legislative Council, he was able to convince the Secretary of State for the Colonies to allow him to name the five appointed members of the council (despite the opposition of the Governor, Sir Edward Betham Beetham). This gave him a clear majority in the Legislative Council. Williams was thus elected Chief Minister and was also able to get all seven of his ministers elected.

Federation and independence

After the Second World War, the British Colonial Office had preferred that colonies move towards political independence in the kind of federal systems which had appeared to succeed since the Confederation of Canada, which created the Dominion of Canada, in the nineteenth-century. In the British West Indies this imperial goal coincided with the political aims of the nationalist movements which had emerged in all the colonies of the region during the 1930s. The Montego Bay conference of 1948 had declared the common aim to be the achievement by the West Indies of "Dominion Status" (which meant constitutional independence from Britain) as a Federation. In 1958, a West Indies Federation emerged out of the British West Indies, which with British Guiana (now Guyana) and British Honduras (now Belize) choosing to opt out of the Federation, left Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago as the dominant players. Most political parties in the various territories aligned themselves into one of two Federal political parties - the West Indies Federal Labour Party (led by Grantley Adams of Barbados and Norman Manley of Jamaica) and the Democratic Labour Party (led by Manley's cousin, Sir Alexander Bustamante). The PNM affiliated with the former, while several opposition parties (the People's Democratic Party, the Trinidad Labour Party and the Party of Political Progress Groups) aligned themselves with the DLP, and soon merged to form the Democratic Labour Party of Trinidad and Tobago.

The DLP victory in the 1958 Federal Elections and subsequent poor showing by the PNM in the 1959 County Council Elections soured Williams on the Federation. Lord Hailes (Governor-General of the Federation) also over-ruled two PNM nominations to the Federal Senate in order to balance a disproportionately WIFLP-dominated Senate. When Bustamante withdrew Jamaica from the Federation, this left Trinidad and Tobago in the untenable position of having to provide 75% of the Federal budget while having less than half the seats in the Federal government. In a famous speech, Williams declared one from ten leaves nought. Following the adoption of a resolution to that effect by the PNM General Council on January 15, 1962, Williams withdrew Trinidad and Tobago from the West Indies Federation. This action led the British government to dissolve the Federation.

In 1961 the PNM had introduced the Representation of the People Bill. This Bill was designed to modernise the electoral system by instituting permanent registration of voters, identification cards, voting machines and revised electoral boundaries. These changes were seen by the DLP as an attempt to disenfranchise illiterate rural voters through intimidation, to rig the elections through the use of voting machines, to allow Afro-Caribbean immigrants from other islands to vote, and to gerrymander the boundaries to ensure victory by the PNM. Opponents of the PNM saw "proof" of these allegations when A.N.R. Robinson was declared winner of the Tobago seat in 1961 with more votes than there were registered voters, and in the fact that the PNM was able to win every subsequent election until the 1980 Tobago House of Assembly Elections.

The 1961 elections gave the PNM 57% of the votes and 20 of the 30 seats. This two-thirds majority allowed them to draft the Independence Constitution without input from the DLP. Although supported by the Colonial Office, independence was blocked by the DLP, until Williams was able to make a deal with DLP leader Rudranath Capildeo which strengthened the rights of the minority party and expanded the number of Opposition Senators. With Capildeo's assent, Trinidad and Tobago became independent on August 31, 1962.

Independence era

Black Power

Between 1968 and 1970 the Black Power movement gained strength in Trinidad and Tobago. The leadership of the movement developed within the Guild of Undergraduates at the St. Augustine Campus of the University of the West Indies. Led by Geddes Granger, the National Joint Action Committee joined up with trade unionists led by George Weekes of the Oilfields Workers' Trade Union and Basdeo Panday, then a young trade union lawyer and activist. The Black Power Revolution got started during the 1970 Carnival. In response to the challenge, Williams countered with a broadcast entitled I am for Black Power. He introduced a 5% levy to fund unemployment reduction and established the first locally-owned commercial bank. However, this intervention had little impact on the protests.

On April 6, 1970 a protester was killed by the police. This was followed on April 13 by the resignation of A.N.R. Robinson, Member of Parliament for Tobago East. On April 18 sugar workers went on strike, and there was talk of a general strike. In response to this, Williams proclaimed a State of Emergency on April 21 and arrested 15 Black Power leaders. In response to this, a portion of the Trinidad Defense Force, led by Raffique Shah and Rex Lassalle mutinied and took hostages at the army barracks at Teteron. Through the action of the Coast Guard the mutiny was contained and the mutineers surrendered on April 25.

Williams made three additional speeches in which he sought to identify himself with the aims of the Black Power movement. He re-shuffled his Cabinet and removed three Ministers (including two White members) and three senators. He also introduced the Public Order Act which reduced civil liberties in an effort to control protest marches. After public opposition, led by A.N.R. Robinson and his newly created Action Committee of Democratic Citizens (which later became the Democratic Action Congress), the Bill was withdrawn. Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips offered to resign over the failure of the Bill, but Williams refused his resignation.

- See Black Power Revolution

Legacy

Academic contributions

Eric Williams was a descendant from the de Boissiere family which made its fortune trading African slaves illegally after slave trading had been abolished in 1807. Williams specialised in the study of the abolition of the slave trade. In 1944 his book Capitalism and Slavery argued that the British abolition of their Atlantic slave trade in 1807 was motivated primarily by economics—rather than by altruism or humanitarianism. By extension, so was the emancipation of the slaves and the fight against the trading in slaves by other nations. As industrial capitalism and wage labor began to expand, eliminating the competition from slavery became economically advantageous.

Before Williams the historiography of this issue had been dominated by (mainly) British writers who generally were prone to depict Britain's actions as unimpeachable. Indeed, Williams' impact on the field of study has proved of lasting significance. As Barbara Solow and Stanley Engerman put it in the preface to a compilation of essays on Williams, which is based on a commemorative symposium held in Italy in 1984, Williams "defined the study of Caribbean history, and its writing affected the course of Caribbean history... Scholars may disagree on his ideas, but they remain the starting point of discussion... Any conference on British capitalism and Caribbean slavery is a conference on Eric Williams."

In addition to Capitalism and Slavery, Williams produced a number of other scholarly works focused on the Caribbean. Of particular significance are two published in the 1960s long after he had abandoned his academic career for public life: British Historians and the West Indies and From Columbus to Castro. The former, based on research done in the 1940s and initially presented at a symposium at Atlanta University, sought to debunk British historiography on the region and to condemn as racist the nineteenth and early twentieth century British perspective on the West Indies. Williams was particularly scathing in his description of the nineteenth century British intellectual Thomas Carlyle. The latter work is a general history of the Caribbean from the 15th through the mid-20th centuries. Curiously, it appeared at the same time as a similarly titled book (De Cristóbal Colón a Fidel Castro) by another Caribbean scholar-statesman, Juan Bosch of the Dominican Republic.

Williams sent one of 73 Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to NASA for the historic first lunar landing in 1969. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. Williams wrote, in part, "It is our earnest hope for mankind that while we gain the moon, we shall not lose the world."

The Eric Williams Memorial Collection

The Eric Williams Memorial Collection (EWMC) at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago was inaugurated in 1998 by former US Secretary of State Colin Powell. In 1999, it was named to UNESCO’s prestigious Memory of the World Register. Secretary Powell heralded Dr. Williams as a tireless warrior in the battle against colonialism, and for his many other achievements as a scholar, politician and international statesman.

The Collection consists of the late Dr. Williams' Library and Archives. Available for consultation by researchers, the Collection amply reflects its owner’s eclectic interests, comprising some 7,000 volumes, as well as correspondence, speeches, manuscripts, historical writings, research notes, conference documents and a miscellany of reports. The Museum contains a wealth of emotive memorabilia of the period and copies of the seven translations of Williams’ major work, Capitalism and Slavery, (into Russian, Chinese and Japanese [1968, 2004] among them, and a Korean translation was released in 2006). Photographs depicting various aspects of his life and contribution to the development of Trinidad and Tobago complete this extraordinarily rich archive, as does a three-dimensional re-creation of Dr. Williams’ study.

Dr. Colin Palmer, Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University, has said: “as a model for similar archival collections in the Caribbean…I remain very impressed by its breadth...[It] is a national treasure.” Palmer’s new biography of Williams up to 1970, Eric Williams and the Making of the Modern Caribbean, published by the University of North Carolina Press, is dedicated to the Collection.

Criticism

Some state, that the economic decline in the West Indies was consequently more likely to have been a direct result of the suppression of the slave trade. Such a criticism can itself, however, be overturned by noting that the apparent prosperity of these British colonies was only a temporary artifact of the revolutionary turmoil in Haiti, which made the British West Indies for a brief while seem more profitable. Williams' evidence showing falling commodity prices as a rationale can largely be discounted; the falls in price led to an increase in demand, raising overall profits for the importers. Profits for the slave traders remained at around ten percent on investment and displayed no evidence of declining. Land prices in the West Indies, an important tool for analysing the economy of the area did not begin to decrease until after the slave trade was discontinued. Supporters of Williams would note, however, that this apparent rise of land prices was merely due to wartime inflation.

It is thus a matter of dispute whether the sugar colonies were in terminal decline after the American Revolution. Their apparent economic prosperity in 1807 can be interpreted, as suggested above, in two ways. It should be noted that Williams was heavily involved in the movements for independence of the Caribbean colonies and had a fairly obvious motive to impugn the colonial power. Indeed, Williams' reputation among black West Indian scholars was always high.

A third generation of scholars led by Seymour Drescher and Roger Anstey have discounted many of Williams' arguments. They do however acknowledge that morality had to be combined with the forces of politics and economic theory to bring about the end of the slave trade.

On the other hand, Williams' central point that the rise of industrial capitalism in Britain was fueled by West Indian slavery, and that, in turn the new industrial bourgeoisie saw the maintenance of slavery as a drag on their profits, both still have some merit. In particular, we should note that significant decline in the British West Indies dates to after the abolition of the Corn Laws by the British in 1846 (one of the imperial preferences abolished was that in sugar).

Richardson (1998) finds Williams's claims regarding the Industrial Revolution are greatly exaggerated, for profits from the slave trade amounted to less than 1% of total domestic investment in Britain.[1]

Williams was frequently lampooned in the paintings of his countryman Isaiah James Boodhoo.

Notes

- ↑ David Richardson, "The British Empire and the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1660-1807," in P.J. Marshall, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume II: The Eighteenth Century (1998) pp 440-64.

References

- Eric Williams. 1944. Capitalism and Slavery Richmond, Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

- Eric Williams. 1964. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. Port of Spain ISBN 1-881316-65-3

- Eric Williams. 1964. British Historians and the West Indies, Port of Spain.

- Solow, Barbara + Engerman, Stanley (eds). 1987. British Capitalism & Caribbean Slavery: the Legacy of Eric Williams.

- Cudjoe, Selwyn. 1993. Eric E. Williams Speaks: Essays on Colonialism and Independence ISBN 0-87023-887-6

- Drescher, Seymour. 1977. Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition

- Meighoo, Kirk. 2003. Politics in a Half Made Society: Trinidad and Tobago, 1925-2002 ISBN 1-55876-306-6

- Rahman, Tahir (2007). We Came in Peace for all Mankind- the Untold Story of the Apollo 11 Silicon Disc. Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1585974412.

External links

- Eric Williams Memorial Collection Homepage

- Eric Eustace Williams in the Digital Library of the Caribbean

- Williams, Eric. Capitalism and Slavery Richmond, Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

| Preceded by Albert Gomes |

Chief Minister of Trinidad and Tobago 1956–1959 |

Succeeded by none |

| Preceded by none |

Premier of Trinidad and Tobago 1959–1961 |

Succeeded by none |

| Preceded by none |

Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago 1962–1981 |

Succeeded by George Chambers |

|

|||||||||